A rare case of the analytics saying twos are good.

Note: To optimally view the visualizations used below, access this article on a computer.

Against DePaul, Northwestern’s dynamic duo of Brooks Barnhizer and Nick Martinelli combined for 44 points. Just three of those came from beyond the arc.

That’s nothing new for the 2024-25 Wildcats. Three-point shooting, although key in Northwestern’s win against UNLV and Northwestern’s ability to stay with Iowa in the Big Ten opener, is not a fundamental focus of this squad’s offense. If you’re an analytics junkie, you’re probably yelling at the ‘Cats from your seat at Welsh-Ryan Arena or in front of your television at home to take more treys.

But that’s not what this year’s Northwestern squad is about. And for once, the math actually agrees with what at first glance may seem like a rejection of analytics in favor of an old-school renaissance.

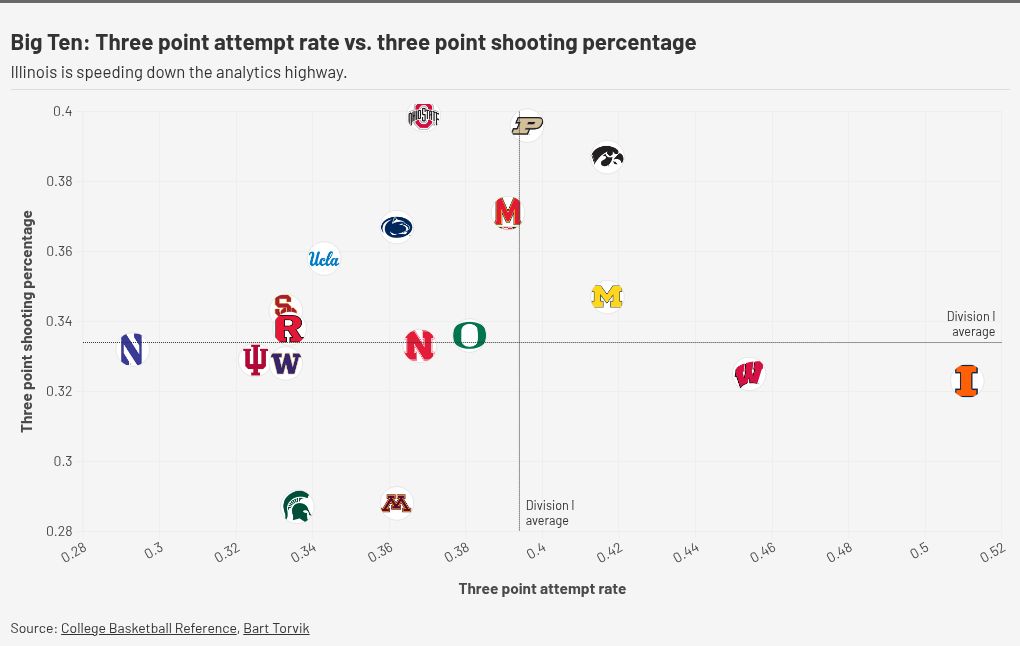

Northwestern is the Big Ten’s most two-point centric offense, with just 29.3% of its field goal attempts coming from three-point land. That’s tied for the 12th lowest mark in the country. The Wildcats have the conference’s lowest three-point attempt rate, a stark change in style from Illinois’ attack that takes threes on over half of its offensive possessions.

From an efficiency perspective, the Wildcats are a pretty average three-point shooting team, not just from a conference perspective but from a Division I perspective. That would suggest shooting more threes to be closer to the pack of Rutgers, USC, Indiana and Washington would be beneficial. But Chris Collins understands his personnel and its capabilities.

“Basketball can be won in different ways,” Collins said after Northwestern’s 84-64 win over DePaul. “The way our team is built, we have really good midrange and in the paint players and that that’s how we’re going to play.”

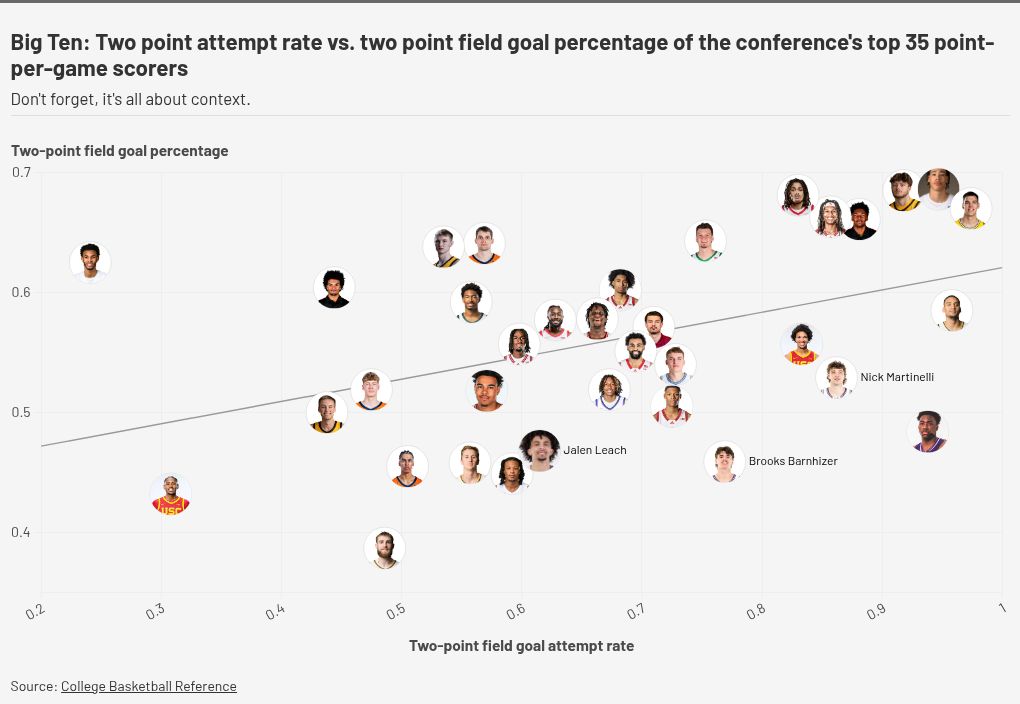

Of the Big Ten’s top 35 point-per-game scorers, Northwestern’s big three of Barnhizer, Martinelli and Jalen Leach all rank in the top-21 in two-point field goal attempt rate. That may not sound super impressive, but that’s naturally a statistic dominated by big men who take every field goal attempt within two feet of the basket. Look at the swarm of big fellas in the top right-hand corner led by Michigan’s Vladislav Goldin at the far right. That description does not match Martinelli, Barnhizer or Leach.

Leach and Barnhizer are significantly below the trend line because they’re much more mid-range focused, which is inherently a less effective shot than looks at the rim by guards that do more of their scoring work inside like Dylan Harper and John Blackwell. Leach especially looks for the midrange game with 32% of his field goal attempts coming from there. That mark ranks in the country’s 97th percentile, and his 42.5% field goal percentage from midrange jumpers ranks in the nation’s 69th percentile per CBB Analytics. Those are efficient shots for him, and if defenses like Illinois are willing to play drop coverage, that’s where the Wildcats feast.

Martinelli is a little bit of a different story. With 86% of his shots coming from two-point range, he’s approaching big man territory. But Martinelli is 6-foot-7, considerably shorter than some of those guys in the top right who are attempting almost all of their shots in tight. Yet no matter how easy Martinelli’s flippers look, they’ll never be as efficient as dunks and under-the-basket layups. Still, Martinelli is attempting 13.1 twos per game (100th percentile per CBB Analytics) and ranks in the 96th percentile or higher in field goal attempts at the rim, in the paint (outside of 4.5 feet) and in the midrange. And although he’s just a 29th percentile finisher within 4.5 feet (58.7%), he’s a 59th percentile paint (outside of 4.5 feet) finisher and an 86th percentile midrange finisher.

In other words, Northwestern is dominating the inefficient shot game. Based on personnel, the Wildcats have turned inefficient shots into effective volume scoring options. It’s just the latest example of Collins fitting his offense to his personnel.

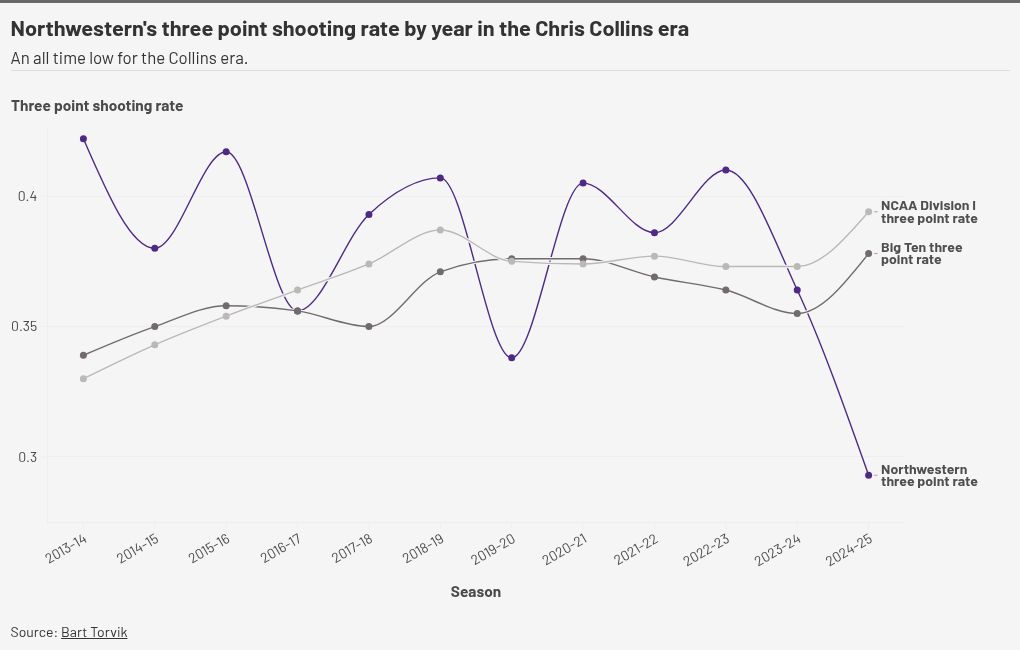

Over the past three seasons, Northwestern’s three-point focus has dipped, surprisingly so even with last year’s trio of Boo Buie, Ty Berry and Ryan Langborg who helped Northwestern become the Big Ten’s first team ever to have three players shoot at least 40% from deep on a minimum of five attempts a night.

And as we’ve seen both the Big Ten and the country become more three-point focused, including a sizable 2.1-point hike in three-point shooting rate nationwide this season, it may seem concerning that Northwestern’s lowest three-point-minded squad of the Collins era is coming at a time where there is the highest three-point rate in over a decade. But as nice as it would be to continue spinning the “three-point shooting is the answer to basketball’s problems” storyline, Collins knows what he’s doing.

Drop any preconceived notions aside and do a little thought experiment. Ideally, a team wants to shoot a certain number of twos and threes such that on any given possession, the expected points from shooting a three are equal to the expected points from shooting a two. This optimal arrangement mathematically maximizes a team’s scoring output by saying the marginal benefit from shooting a three is equal to the marginal benefit from shooting a two.

If that doesn’t make sense, suppose there was a sizable gap between the expected points per possession from shooting a three compared to shooting a two. Then, a team would rely more heavily on the method that yields more expected points until that method loses efficiency to the point where the expected points per possession of each method are equivalent.

We’ll assume that the more three-pointers a team attempts, it might be forcing the issue so you’d expect to see a team’s three-point field goal percentage decrease. This is backed up by teams like Illinois and Wisconsin in the first visual.

If a squad is at that optimal balance, there should be no difference in a team’s scoring output between theoretically only shooting twos at its current two-point shooting clip compared to theoretically only shooting threes at its current three-point shooting percentage for an entire game.

We can do this by creating theoretical games where Northwestern shoots twos on every possession (assuming its current two-point field goal percentage) and compare it to if it only shot threes (assuming its current three-point field goal percentage). We also have to assume each possession is independent, such that a defense has no knowledge if a team is about to shoot a three or a two. This equation has no offensive rebounds, second-chance points or fouls. Obviously, fouls are more likely on two-point attempts, making teams more willing to attack the hoop, not only increasing the benefit from a two-point attempt but on the opposite end, potentially opening up good looks from three. However, we’ll ignore fouls for simplicity’s sake. This is pure math.

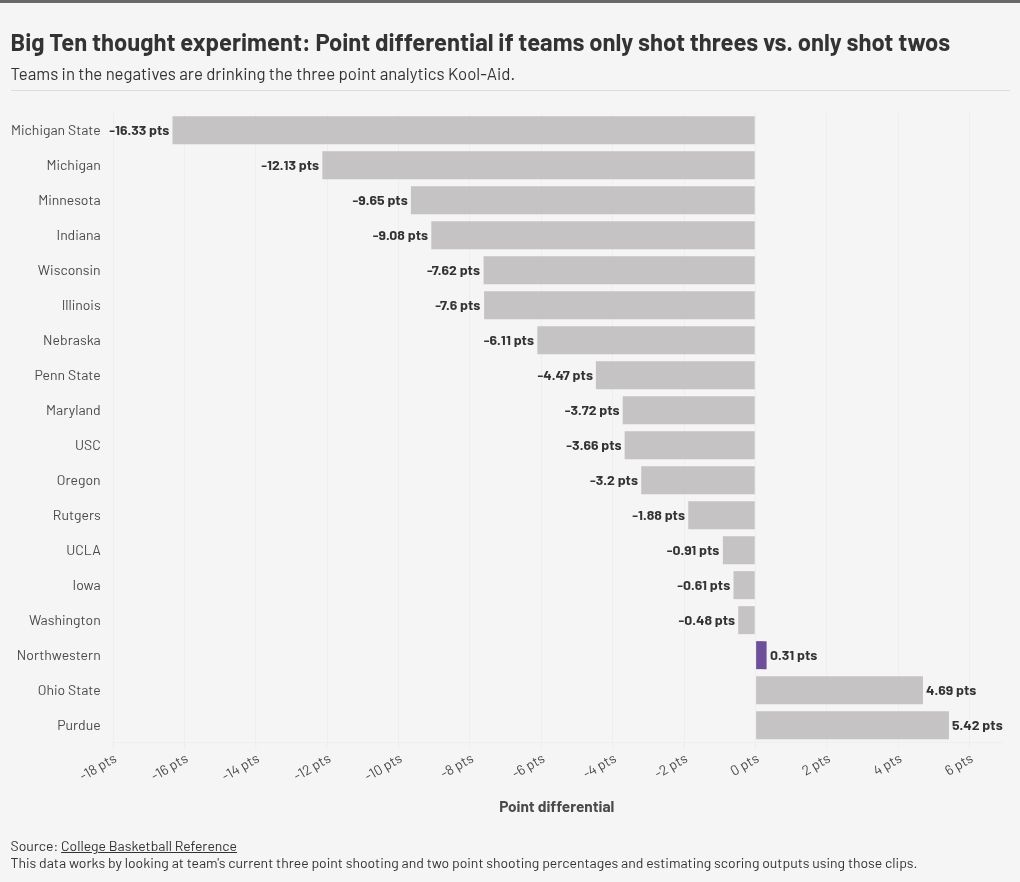

Northwestern averages 66.8 possessions a game. Only 57.6 of them are usable after subtracting 9.2 turnovers a contest. Taking into account a 49.5% two-point field goal percentage, if Northwestern only attempted twos on every usable possession, the Wildcats would average 57.06 points per game, not including any potential points from the free throw line. At its current 33.2% clip from deep, if Northwestern only attempted threes on every usable possession, it would average 57.37 points per game. This roughly 0.3-point difference is the smallest in the Big Ten. In other words, Northwestern is shooting the right amount of threes.

When repeating this process for the Big Ten as a whole, Northwestern is one of just three Big Ten teams in the positives, meaning it could theoretically shoot more threes. However, a 0.31-point difference is zero in this model. To cast a wider net, anything inside four or five points is most likely negligible too, given a roughly third of the season sample size. If you’re Michigan State on the other hand, you should probably realize three-point shooting isn’t your thing.

Remember there are plenty of potential biases (not accounting for fouls, offensive rebounds, etc.) within this model too, but it does a good job of taking a macro-level snapshot of where teams are at. It’s simply looking at a team’s current three-point shooting and two-point shooting percentages, assuming those percentages are byproducts of a team’s three-point rate where more three-point shots lead to lower efficiency and extrapolating those numbers over a team’s usable offensive possessions.

If that’s too mathy for you, a non-mathematical look would say: Northwestern’s midrange and two-point focus is fine because the Wildcats dominate other parts of the game unrelated to shot selection.

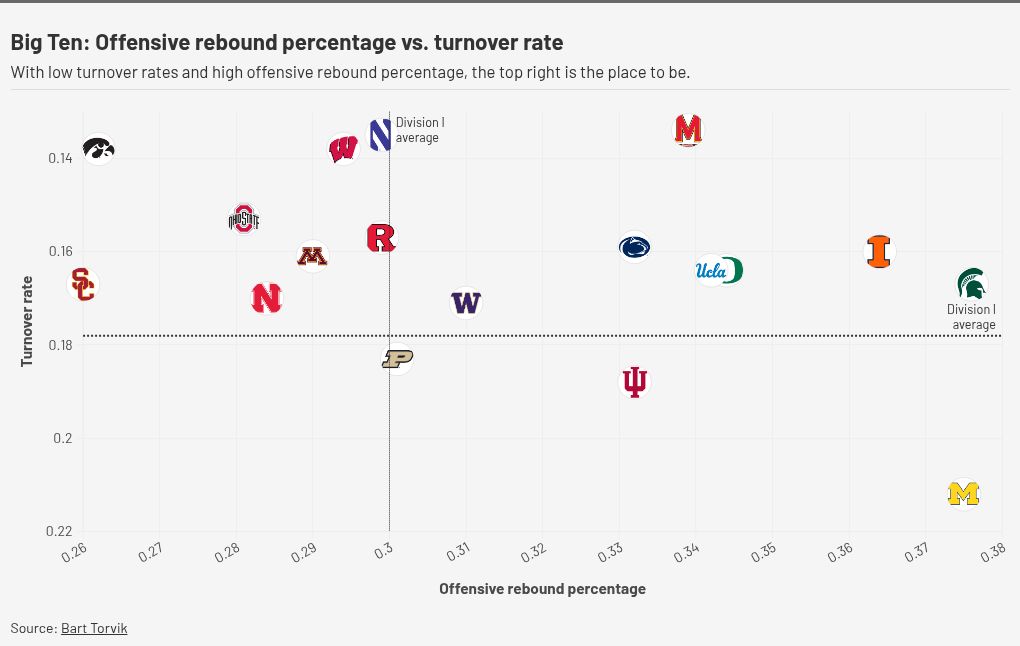

Note that putting offensive rebound percentage and turnover rate on the same graph has no correlation, rather it helps show where Northwestern ranks in two categories that impact offensive output. Turnover-wise, Northwestern averages the least number of turnovers per game in the conference but has the second lowest turnover rate because of its lack of possessions thanks to its slow pace.

If a team is going to take a lot of statistically inefficient midrange twos, every possession is incredibly critical. However, if a team doesn’t lose out on possessions by turning the ball over, it’s okay to take slightly less effective shots. Therefore, Northwestern taking care of the basketball balances out taking midrange and highly contested paint twos.

Northwestern’s relatively mediocre offensive rebound rate might not be much to write home about, but it’s critical for an offense in the 80th percentile in percentage of field goal attempts on putbacks. That’s especially true for Nick Martinelli who seems to constantly compete down low, battling for second chances after missed floaters and flipped shots. For Martinelli, 9.3% of his shots are coming on putback opportunities and 14.2% of his points are second chance efforts. It’s a similar mentality as above. It’s okay to take tough shots if you clean up the glass on misses. Even doing that at an average rate nationally is essential for how midrange-heavy Northwestern plays. In Big Ten play, Northwestern will certainly be challenged against a slew of physical teams that dominate the glass, making every offensive rebound vital for the Wildcats.

There’s also room for improvement elsewhere. Against DePaul and Georgia Tech, Northwestern translated its defensive intensity into easy offense. Over the two-game stretch, the Wildcats racked up 23 steals, scoring 40 fast break points on the other end. However, only 9.9% of Northwestern’s field goal attempts have come in transition, which ranks in the 19th percentile nationwide per CBB Analytics. It’s tough for a team that plays so slowly, but making the most out of steals and forced turnovers is critical for kickstarting an offense so reliant on three scorers.

Plus, Northwestern not only excels when it dictates the pace of play but has found a way to control the pace throughout its current three-game win streak. Against a three-point heavy team like Illinois, slowing the Fighting Illini’s tempo was crucial, while in the first half against Iowa, Northwestern got boat raced and was forced to play catch-up in the second half.

The Wildcats have the defensive structure to raise the floor, but the ceiling of this team inevitably comes down to how efficient Northwestern is offensively. In this three-point-heavy era, finding a balance between its two-point strengths and benefits from extending the floor, dictating the pace of play, limiting turnovers, getting out in transition for easy baskets and making the most of second chance opportunities are the places where Northwestern has made up for its statistically inefficient offensive mindset.

As long as the ‘Cats continue to excel in those areas, there’s nothing wrong with taking twos.