The Northwestern athlete was diagnosed with testicular cancer at the end of his freshman year. Now, he’s inspiring strength and advocacy in those around him.

When Rachel Stratton-Mills surprised Aaron Baltaytis in the hospital, she almost did not recognize the Division I swimmer.

The Northwestern Swimming and Diving coach checked in with Baltaytis every day as he underwent treatment for testicular cancer. He seemed to be the same teenager with the same positive attitude that Stratton-Mills knew well, but phone calls and texts did not reveal the physical effects of multiple rounds of chemotherapy.

“I knew it was him because he was by far the youngest person in the room,” said Stratton-Mills about seeing Baltaytis for the first time since he began treatment. “But it took me a second. Hair was different. Just everything about him. He no longer looked like this athlete I was used to seeing.”

Replace muscle with a few extra pounds that came from the exhaustion and hunger brought on by medication. Replace the chlorine-scented pool deck with a sterile hospital. Keep the focus on the Northwestern swim team. Keep the bond between a coach and an athlete. This was one of the best days of an uncertain summer, as Baltaytis’s return to Northwestern and swimming remained in question.

“Regardless, if he was going to come back and never be able to swim again or be at 100% or be at 50%, we had no idea,” Stratton-Mills said. “But I don’t think there was ever a question that he wouldn’t be back and be part of this team fully, whatever that looked like.”

Walt Middleton/Northwestern Athletics

Baltaytis was just weeks away from completing his freshman year when the lump on his testicle began to hurt.

At 16, Baltaytis first felt this lump, but it was dismissed. At 18, he thought it was getting bigger, but it was misdiagnosed as a hydrocele. But in the spring of 2024, Baltaytis knew this onset of pain was significant.

After having an ultrasound, Baltaytis was scheduled to meet with the doctor the next day, during one of his classes.

“I started freaking out, like what’s going to happen to me,” Baltaytis said. “All I was thinking about was this Data Science class because finals were coming up, and I had to miss class because I was meeting with the doctor. After he told me that I had cancer pretty much, I just ran to my Data Science class. I needed something to get my mind off what was going on.”

Baltaytis began that week with a swim meet on Sunday. On Tuesday, an ultrasound identified a mass. On Wednesday, after being diagnosed with testicular cancer, he was scheduled for a CAT scan, which revealed that his cancer had spread extensively. On Thursday, he was back home in New Jersey. By Friday night, he was recovering from surgery.

But this one tumultuous week was just the beginning. Although his surgery removed the primary tumor, his CAT scan was still riddled with dark spots, representing 27 other tumors.

“Everything up until then was just great,” said Baltaytis about his first year at Northwestern.

Baltaytis loved his teammates and his coaches, and they loved him. He was doing just fine studying economics. Swimming was fun.

The biggest challenge was adjusting to the intensity of swimming at the Division I level, but one that he took on well — he became Northwestern’s primary butterflyer and set personal bests in each of his events by the end of the season.

This diagnosis originally seemed like something that could just be taken care of. Baltaytis was a healthy 18-year-old in peak shape. The idea of him even having cancer was surreal.

“I don’t honestly think it hit me for another couple weeks,” Baltaytis said. “I was using comedy to cope with it, like I just didn’t really understand what was going on. In my own defense, I didn’t really know how extensive the spread was and how bad the treatment would get. I’m like, ‘Okay, I have testicular cancer. I’ll go home, I’ll get it taken care of, I’ll be back in the fall.’”

Baltaytis would be. But it wasn’t that easy.

Rather than spend his summer representing Latvia in the European Championships and gearing up for his sophomore season, Baltaytis underwent 12 weeks of chemotherapy. Four rounds. Three weeks.

Baltaytis would wake up early and eat breakfast. His mother would drive him to Memorial Sloan Kettering in New York City. He would take his medication and then receive chemotherapy, which he mostly slept through. He would come home: sleep, eat and get ready to do it all over again.

For whatever he was going through, and, for anyone, this would be a lot, he was still Aaron.

“He was always in good spirits,” said teammate Diego Nosack. “I loved talking with him, as always. No matter what he was going through, he’s just always such a fun guy.”

This personality is why Stratton-Mills did not think the treatment had caused any noticeable physical effects. Meanwhile, appearance was one of the biggest impacts of all.

Baltaytis could, of course, no longer swim and intensely work out, but he was also constantly hungry from his medication. During chemotherapy, his muscles faded, and he gained 10 to 15 pounds.

“Just seeing my physical changes, like not becoming this Division I in shape athlete anymore and kind of just a chemo, cancer patient was really the hard part,” Baltaytis said.

When he was not receiving treatment, Baltaytis kept busy.

He got his exercise fix from playing pickleball and golf. He got his swimming fix from coaching. Even during his final rounds of chemo, he coached for his former club team for two hours each night.

The result of Baltaytis’s battle was still yet to be determined. His tumors were teratomas, meaning they were chemo-resistant. The chemotherapy was simply a precaution. Baltaytis needed a second surgery.

“His one goal through all of this is, ‘I just want to be back at school with my friends in September,’” Stratton-Mills said. “He didn’t want to let this take him off that path, and I think the truth is he would never let it, and that’s his resilience. His goal is to just be one of the guys and be on this team and not have anything be different.”

This goal of a return to normalcy, and the belief that it would happen, was consistent. This was, after all, a teenager who finished his classes online even though he was just diagnosed with cancer.

In August, three Northwestern teammates — Nosack, Stuart Seymour and David Vinokur — visited New Jersey to help make what Baltaytis called “the best week of [his] life.” Nosack delayed his trip home to Oregon in order to make it work, with the trip sandwiched between Baltaytis’s final round of chemo and his upcoming surgery.

“I had not been home since December, but I told my parents and my family that I needed to go see him first before I was able to do anything else,” Nosack said.

The gesture touched Baltaytis, and for a few days, it was a welcome return to normalcy. They explored New York City, watched movies, went to a Yankees game and in classic fashion, teased each other.

“They were still making fun of me,” Baltaytis said. “I wasn’t totally bald. I had some fuzz on top. They were always like rubbing it and pinching my cheeks, and I was chubby. Just knowing that they still treated me like one of the guys was great.”

NU Athletics

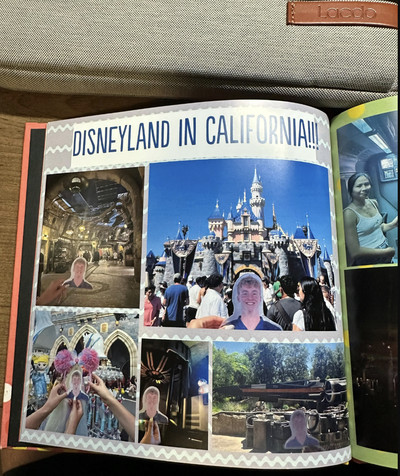

Whether it be a cross-country trip like this one, the frequent check-in texts or bringing a photo of Baltaytis around the world in a “Flat Stanley” concept, Northwestern Swimming and Diving rallied around him.

Baltaytis had parents who were completely devoted to him every single day and siblings who carved out time to be with and help their brother, but his Northwestern family, though hundreds of miles and even oceans away, also adopted this fight. Especially his coach.

“It’s really important that these athletes know we care about them as humans first and student-athletes second,” said Stratton-Mills about visiting Baltaytis. “In essence, it’s almost the opposite of peak athletic performance, battling illness, and for me, it was just a no-brainer. How could I have one of my athletes in the hospital, going through chemo, going through all this treatment, and how could I not go and show my support?”

August 28 was the day circled on the calendar. Baltaytis’s second surgery could have two outcomes: he could need another two rounds of chemotherapy or everything could be removed.

“Honestly, I wasn’t even thinking about the surgery,” Baltaytis said. “I was just begging, like, ‘Please no more chemo. I’m so done with this. I can’t do two more rounds.’”

After a nine-hour abdominal surgery, all 27 tumors were successfully removed.

Almost right after waking up from anesthesia, Baltaytis dialed his coach. He was in a foggy state but had a smile on his face.

“I did not think he would be calling yet, like that’s how close it was to his mom saying surgery was over,” Stratton-Mills said. “[The call] really made no sense, but the key was I knew he was okay, and I knew he was going to be okay.”

On September 18, a cancer-free Baltaytis returned to Northwestern and his teammates and friends, who were waiting to help him move in.

All Baltaytis wanted was to be back. Now, he was. And swimming would soon follow.

Baltaytis had not been in a pool since he was diagnosed with cancer. He couldn’t swim during treatment, and he needed to wait 12 weeks for his abdominal scar to heal before he could exercise.

On November 20, exactly 12 weeks after his surgery, Baltaytis jumped into the pool. It was nothing more than splashing around, and Baltaytis said it was as though he “forgot to swim.” With his team and coaches gathered around, it was almost poetic that he felt like he was starting anew.

Baltaytis had not swum in nearly six months. He was down 20 pounds from when he was initially diagnosed. He had been through the unthinkable.

“There’s no textbook on how to help a 19, 20-year-old come back to Division I athletics post chemo,” Statton-Mills said.

This was a new beginning, but it represented human strength and a newfound appreciation for each day.

Baltaytis understandably had to take his return slowly, working up his yardage in the pool and building back muscle. As a result, he decided to redshirt the 2024-25 season in order to gain an extra year of eligibility. But it would not do Baltaytis justice to say that these months have been about catching up to his old self. The work he has put in and continues to put in is about being as good as he possibly can be.

“I would say he’s already faster and stronger than he was before everything happened,” Nosack said.

Stratton-Mills said Baltaytis is at “full go,” as he prepares to return next season. He currently does eight swims and three lifts a week, and this summer, he will be racing in non-collegiate meets. In the midst of all this, Baltaytis was also the only one of the 61 Wildcat athletes with All-Academic Big Ten honors in the winter to post a perfect GPA.

While he’s focused on making the most of these next few years, his sights are on a master’s degree and qualifying for an NCAA Championship – improving upon being just over half a second off from qualifying for the 100-yard backstroke in 2024.

But Baltaytis’s presence has impacts that extend far beyond just himself. He’s a beacon of encouragement and advocacy.

Baltaytis has reached out to other swimmers battling illness, passing along the support that five-time Olympic gold medalist and testicular cancer survivor Nathan Adrian offered him. And whether he realizes it or not, he offers the same encouragement to his teammates.

“Whenever I get the chance, I always go in his lane because he is such an uplifting person,” Nosack said.

Nosack also described a culture change sparked by Baltaytis. There is an increased willingness to be vulnerable and a shared understanding that the team is there to help, Nosack said. Baltaytis knows the importance of this and wants his teammates to value it too, especially given that men’s health is not widely discussed.

“I want everyone, obviously men included, but everyone just to advocate for themselves because you have intuition about yourself,” Baltaytis said. “You really just need to fight for yourself because nobody’s going to be there for you if you’re not.”

Stratton-Mills said she hopes Baltaytis’s legacy spreads throughout the athletic department, because his story shows it is possible “to get through and thrive through” adversity.

This attitude fits into another one of Baltaytis’s goals: living life to the fullest.

“[Baltaytis] has a sticky note on his locker that says, ‘Every day is a blessing,’” Nosack said. “When I first saw it, I was almost tearing up. Just talking about it now, like you can’t take anything for granted.”