Another year of great change for the team.

Frank Chance, the “Peerless Leader,” was let go in a dispute with owner Charles W. Murphy after 1912 — while he was hospitalized about to have brain surgery!

Another of the famed Cubs from the previous decade’s successful teams, Johnny Evers, was named manager. The Cubs did all right early on, but wound up finishing third, far out of first place.

And some other deals made in this year would affect the team’s direction going forward.

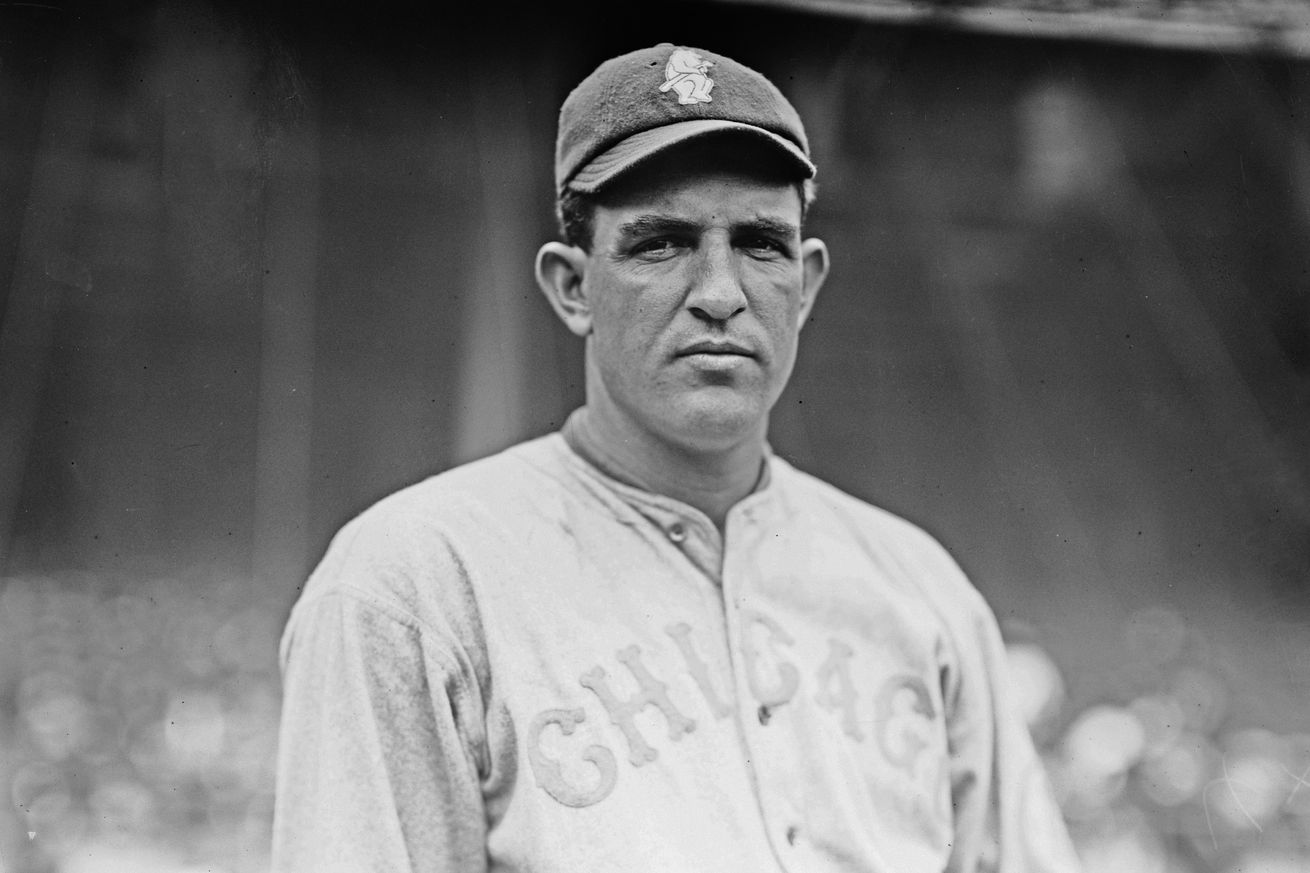

January 6: Signed Roger Bresnahan as a free agent

Bresnahan had actually previously been with the Chicago NL club (not yet called “Cubs”) in 1900 and played two games for them. Released, he went on to a Hall of Fame career with the Giants and Cardinals, playing in the World Series for the Giants in 1905 (and would have in 1904, had manager John McGraw not pigheadedly avoided playing the AL champion A’s).

The Cardinals released Bresnahan in November 1912, and in three seasons with the Cubs he batted .239/.345/.306 in 249 games, and managed the team to a losing record in 1915.

Bresnahan is widely credited with helping to create the types of catcher’s gear normally worn today, particularly shin guards and padded masks. A legitimately great player when younger, his Cubs tenure wasn’t much as a player and controversial as a manager.

April 11: Sent Jimmy Sheckard to the Cardinals for cash considerations

In seven years with the Cubs, Sheckard, their regular left fielder, played for four pennant winners and on two World Series champions, producing 19.1 bWAR and batting .239/.345/.306 with 163 stolen bases. The stolen-base total ranks 17th in franchise history. This was another move that was part of the dismantling of all those champioship teams.

July 1: Sent Fred Toney to Louisville (American Association) for cash considerations

This was a mistake. Toney pitched only briefly for the Cubs for three seasons (1911-13) and posted a 4.02 ERA in 34 games (11 starts).

After a year at Louisville, Toney was selected by the Dodgers in the 1914 Rule 5 Draft and they let him go to the Reds on waivers.

Another mistake — Toney had four good years with the Reds and five with the Giants, posting a total of 28.4 bWAR and 124 wins in those nine years. In 1917 he famously threw a no-hitter against the Cubs May 2, the game that was once called the “double no-hitter” because Hippo Vaughn of the Cubs took a no-no into extra innings.

Toney also pitched in the World Series for the Giants in 1921. The Cubs should have kept him.

August 5: Acquired Eddie Stack and cash considerations from the Dodgers for Ed Reulbach

Reulbach won 136 games and posted 28.1 bWAR in nine years with the Cubs, and was one of their top starters for all their pennant-winning teams of the previous decade. From 1905-09 he posted a 1.72 ERA in 175 games (142 starts) covering 1,262 innings, and even for the Deadball Era that was excellent. He was probably the best pitcher in the NL in 1905 when he had a 1.42 ERA and 9.1 bWAR in 291⅔ innings.

By 1913 he was 30 and the innings had taken their toll. He pitched until 1917 and actually had a good year for Newark of the Federal League in 1915.

Stack, a Chicago-area native who appeared to be a decent young pitcher at the time of the deal, wound up with some health issues (likely a “duodenal ulcer,” per his SABR biography), and as was the case with many players in that era, felt he could make a better living elsewhere. He worked as a teacher and administrator in the Chicago Public Schools system for 36 years, in his younger days playing and umpiring in semi-pro ball.

August 8: Transferred the player rights to Orval Overall to San Francisco (Pacific Coast League) for cash considerations

Like Reulbach, Overall had been one of the top starters for all the Cubs pennant winners of the 1906-10 period. He’d skipped pitching in 1911 and 1912 to work in a gold mine in California he owned with his teammate Mordecai Brown. Overall returned to pitching for the Cubs in 1913, but he had too much arm trouble to be really effective and his contract was released to San Francisco after he cleared NL waivers. He pitched in 19 games there and then retired.

Eventually he inherited a citrus farm when his father died, sold it off and became a wealthy man and worked in banking in California until he died of a heart attack in 1947, aged 66.

August 9: Acquired Hippo Vaughn from Kansas City (American Association) for Lew Richie

This is one of the best deals in franchise history.

Richie had three good years for the Cubs from 1910-12, but his performance declined in 1913 and so the Cubs were able to acquire Vaughn from the minor league club in Kansas City. Vaughn had pitched, briefly and not well, for the Yankees and Senators from 1908-12, and Washington had sent him to K.C. in a deal in late 1912.

This worked out very well for the Cubs, who got 40.0 bWAR and 151 wins in nine seasons from Vaughn. He was the best pitcher in the NL in 1918, when he posted 7.7 bWAR and led the league in wins, ERA, innings, shutouts (eight), strikeouts, ERA+, FIP and WHIP. Vaughn’s bWAR total is fifth-best among all Cubs pitchers in the Modern Era, behind Fergie Jenkins, Rick Reuschel, Mordecai Brown and Grover Alexander.

His given name was James, but he became known as “Hippo” due to his size — listed at 6-4, 215, his SABR biography says he might have tipped the scales at nearly 300 pounds later in his career. After Vaughn’s playing career he settled in Chicago and died there in 1966, aged 78.

Richie pitched in one more minor-league season in 1914. He was slated to continue, even possibly pitching for a Federal League club in 1915, but was stricken with tuberculosis, a disease that had killed several members of his family in the previous decade. Never fully recovering, he lived the rest of his life in a sanatorium before dying in 1936, aged 52.

September 20: Acquired Walter Keating and Zip Zabel from the Dodgers for Fred Herbert

This was essentially a deal involving all minor-league players who were associated with the major-league clubs noted. Herbert had never pitched for the Cubs and eventually appeared in only two MLB games, for the Giants in 1915.

Keating, a shortstop, went 4-for-43 (.093) in 26 games for the Cubs from 1913-15.

Zabel posted a 2.71 ERA and 2.4 bWAR in 66 games (25 starts) for the Cubs from 1913-15 and I include him mostly because “Zip Zabel” is a great baseball name. (His real given name was George Washington Zabel, and “Zip” is much better for baseball.)

Zabel does have one accomplishment worth noting. On June 17, 1915 at West Side Grounds, the Cubs were playing the Dodgers. Bert Humphries, the Cubs starter, had to leave the game with an injury with two out in the first inning and Zabel relieved him. Humphries had allowed one run; the Cubs scored two in the bottom of the first and led 2-1, but the Dodgers tied things up in the eighth. Both teams scored a run in the 15th and the Cubs eventually pushed across a run in the 19th to win 3-2… with Zabel still pitching. Tribune scribe I.E. Sanborn wrote:

Zabel took the slab job only partially warmed up when a sharp bounder disabled Humphries’ pitching hand in the opening inning, after the Robins had scored one run. The tall chemist from Kansas zipped the ball around the bats of the visitors with such precision and effect that they should never have scored another run during the day. He pitched a brilliant game, holding the Robins to nine hits in more than eighteen innings, and allowing himself to be master of the situation always. Not a man walked on him except for the batsman he passed intentionally in a pinch in the fifteenth inning, when defeat stared the Cubs in the eyes.

As I’ve said before — they sure don’t write ‘em like that anymore.

Zabel’s 18⅓-inning relief appearance, more than 110 years later, remains the record for the longest relief outing in major-league history. (And given the current Manfred Man rule and the way bullpens are handled, probably will remain so forever.)

He had an interesting post-baseball life, using the background in chemistry noted by Sanborn, which started not long after that game, because as you can imagine, arm trouble began. Then he got misused by manager Roger Bresnahan and apparently didn’t fit into Cubs plans when ownership and management changed in 1916. From Zabel’s SABR biography:

By 1926, Zabel had risen to chief metallurgist at Fairbanks-Morse. He would later become superintendent of company foundries, nationwide. George was also active in the American Society for Steel Testing, an industry educational association, and a frequent lecturer on scientific subjects. By the 1940s, his research on electric plating and spectrograph analysis had earned Zabel an entry in Who’s Who in the Midwest. He retired from Fairbanks-Morse in 1948, and subsequently entered public service. In 1958, Zabel was elected to the first of his five terms to the Rock County (Wisconsin) Board of Supervisors. He also served a term on the Beloit City Council.

Zabel died in Beloit in 1970, aged 79.

These deals did well for the Cubs so I’m going to give them another “A”.